Background

Soft Actuators

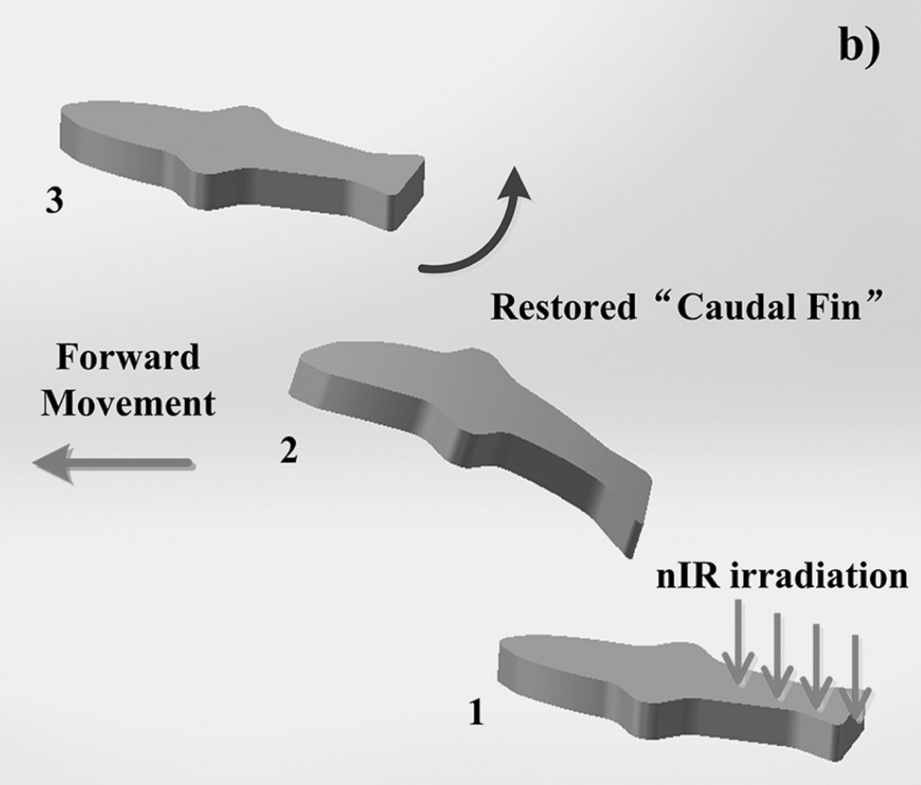

Soft materials have applications in a variety of fields. Their unique properties allow them to navigate soft environments and have mechanical properties necessary for repetitive movement. Some properties that can describe soft materials for actuation are lightweight, flexible, strong, soft, malleable, resistant, and durable. In the biomedical field, soft actuators have been used in applications within the body and external to the body. Soft materials are able to bend in response to its surroundings, and thus, have been studied for biosensors. There has been an increase in studies with optomechanical actuators. This type of actuator is able to respond to light for its motion or morphological change. A study was able to create soft robotic fish that responded to the stimulus of near infrared light (Figure 1) (Weitao Jang et al, 2014). This method of actuation provides advantages in comparison to direct stimulation. There is potential for wireless actuation or shape deformation with a simple to implement stimulus.

Figure 1. Soft robotic fish (Jang et al, 2014)

Chromium dioxide

Chromium dioxide (CrO2) is an interesting material, because it possesses desirable metallic and magnetic properties. The electrical conductivity of CrO2 is high compared to other oxide metals, and it is comparable to conductors made of Mn and Gd at room temperature (Chamberland BL, 2006). CrO2 is also ferromagnetic at room temperature, which gives it a high susceptibility for magnetization. Additionally, CrO2 has a relatively low Curie temperature of 391 K, in comparison to other magnetic metals: 857 K for magnetite Fe3O4 (Shpak et al, 2009), 1,043 K for iron, 1,394 K for cobalt, and 631 K for nickel (Buschow KHJ et al, 2001). A magnetic material loses its random magnetization when it reaches its Curie temperature. With small changes in temperature, the magnetization of CrO2 can be decreased significantly. Metal alloys with a Curie temperature as low as 310 K, including iron and nickel, can be brittle and lack the mechanical flexibility required in soft robotics and actuators.

Magnetic Actuators

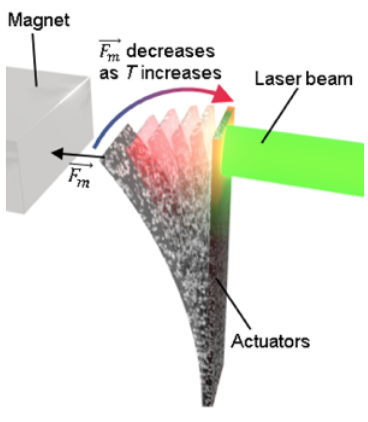

Due to the magnetic properties of CrO2, it has been explored as a material for magnetic actuators. In a study, a magnetic cantilever film was formed and actuated using a laser (Li M et al, 2018). PDMS is an elastomer commonly used in prototyping, analytical chemistry, and micromechanics (Harsányi G, 2000). It is simple to produce, cost-effective, elastic, and strong. A permanent magnet was used to generate a magnetic field around the cantilever film and induce a force on the film (Figure 2). The magnetic force can be characterized by the equation: F = (m ⋅ ∇), where m is the magnetization of the film; and m can be characterized by the equation: m = (χ/μo)B, where χ is the susceptibility, which is dependent on temperature. As the temperature increases, the susceptibility decreases. This decreases the magnetization and reduces the magnetic force on the film.

Figure 2. Photothermal actuation of cantilever film (Li M et al, 2018)

Spontaneous Curvature

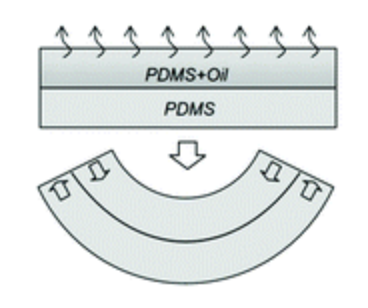

Elastomeric films have been created that incorporate a spontaneous curvature (Egunov AI et al, 2015). These films were created using a bilayer material morphology. PDMS was used as the base of both layers. The study was able to achieve spontaneous curvature of the bilayer films by inducing an imbalance of internal mechanical forces. The top layer included silicone oil, and when extracted, the top layer would contract. This led to curvature of the films (Figure 3). The study found that the contraction of the top layer of the films was dependent on the silicone oil concentration of the top layer. Additionally, the curvature magnitude was shown to correlate to the contraction, and thus the silicone oil concentration.

Figure 3. Bending of bilayer film. After silicone oil extraction, there is contraction in the top layer leading to bending of the film (Egunov AI et al, 2015).

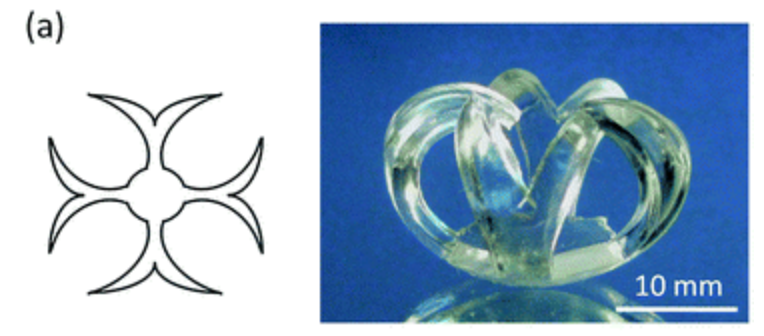

The study was able to use the different curvatures to achieve different geometry, including an enclosing crown (Figure 4). A unique method the study employed was adding localized layers of PDMS + silicone oil on the bilayer films. This allowed them to control the curvature at specific locations for more complex geometries with concrete angles.

Figure 4. Enclosing geometry with spontaneous curvature (Egunov AI et al, 2015).